Light Fountain

By

SRI SWAMI CHIDANANDA

A DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY PUBLICATION

Fifth Edition: 1991

(3,000 copies)

World Wide Web (WWW) Edition : 1999

WWW site: https://www.dlshq.org/

This WWW reprint is for free distribution

© The Divine Life Trust Society

ISBN 81-7052-080-0

Published By

THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY

P.O. Shivanandanagar–249 192

Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttar Pradesh,

Himalayas, India.

CONTENTS

- Publishers’ Note

- Preface

- The Author

- Introduction

- Days Of The Acorn

- The Apostle Of Prayer

- Being And Doing

- Secret Of The Intense Activity

- Lessons On Life

- Real Renunciation: The Fiery Flame

- The Rugged Path

- The Problem Of The Aspirants In Society

- Ever-Alert Vigilance And Vichara

- Precept And Practical Living

- Asceticism And Common-Sense

- What The World Finds

- The World As He Beholds It

- His Destined Role

- “The Only Worship I Know”

- The Medium Of Today

- Echo From The West

- Ecce Homo!

- This I Bequeath

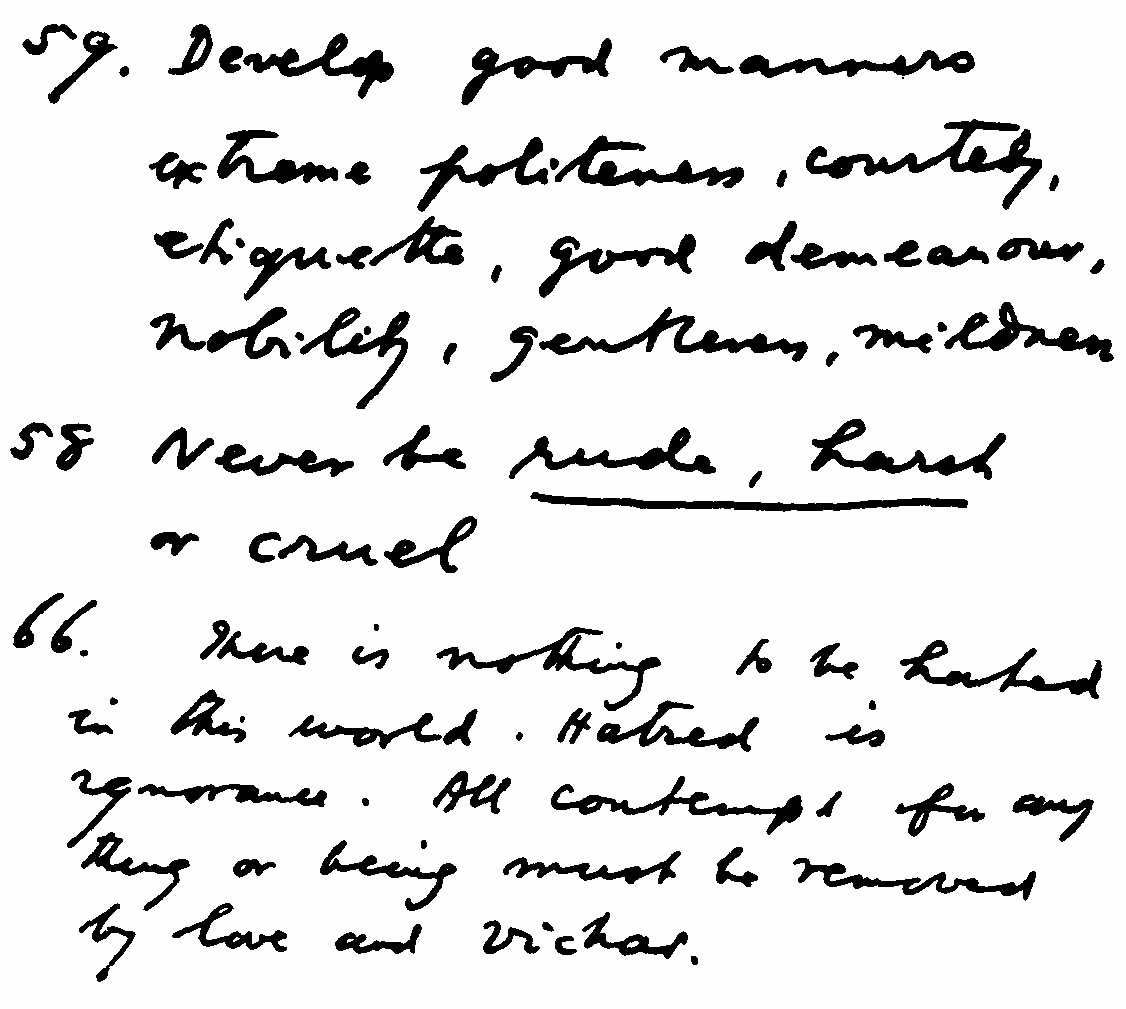

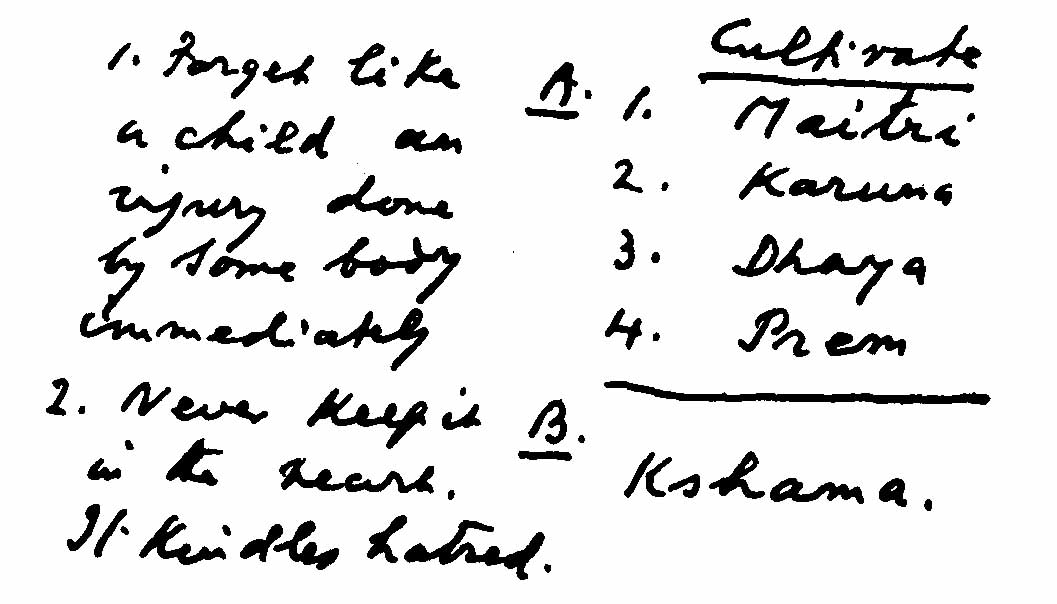

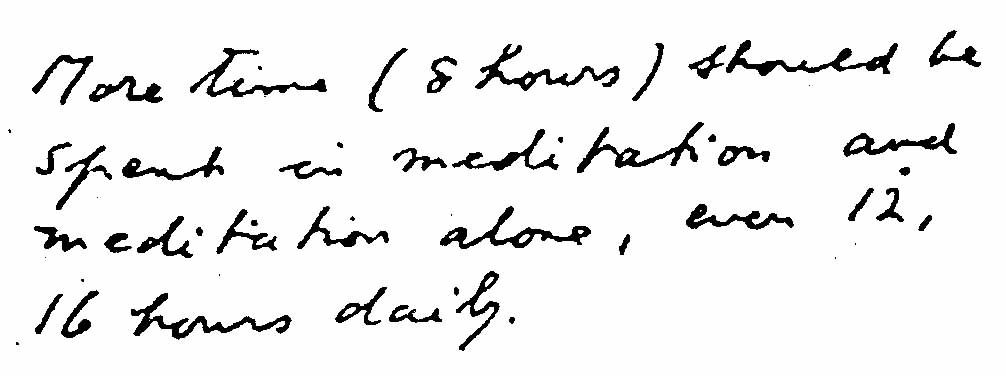

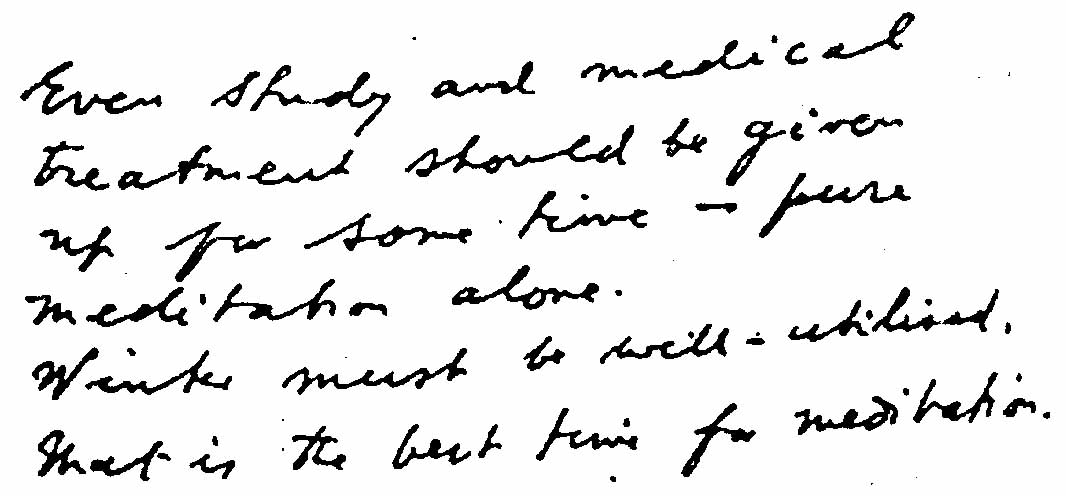

- Pointers On The Pathway

- Light-Fountain

- Epilogue

PUBLISHERS’ NOTE

In this little volume an attempt has been made to present to the public an impartial study of Swamiji’s personality from a consideration of some of the salient incidents of his interesting life–past and present as well. Unlike the two or three books of a biographical nature issued on earlier occasions, the present work mainly aims at bringing out the philosophy underlying and the practical lessons embodied in many of his ordinary activities. Therefore it is in the nature of a development of and a finishing touch to the previous works, rather than a mere narration of his career. Written somewhat in an analytical vein, very many helpful and guiding hints have been brought out: they are certain to be of immense practical value to every class of reader. Herein lies its distinctive worth. It also brings to light some beautiful traits of Sri Swamiji, known little hitherto, as a many-sided model of the Ideal Man.

—THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY.

PREFACE

Blessings come slowly but when do they come they shower upon you in plenty. They have done so in my case. On top of all, I have had the crowning good fortune of being chosen by Him to engage in a work that is certain to prove of service to not a few. Considering it a rare privilege to write about one who is a leading light both to India and to the world of today, I am launching forth this work with pleasure. The purpose of the book, the introduction makes amply clear. Even if a fraction of it is fulfilled, I shall be thrice blessed indeed.

SWAMI CHIDANANDA.

THE AUTHOR

Sridhar Rao, as Swami Chidananda was known before taking Sannyasa, was born to Srinivasa Rao and Sarojini on 24th September, 1916, the second of five children and the eldest son. Srinivasa Rao was a prosperous Zamindar owning several villages, extensive lands and palatial buildings in South India. Sarojini was an ideal Indian mother, noted for her saintliness.

At the age of eight his life was influenced by one Anantayya, a friend of his grandfather, who used to relate to him stories from the epics, Ramayana and Mahabharata. Doing Tapas, becoming a Rishi, and having a vision of the Lord became ideals which he cherished.

His uncle, Krishna Rao, shielded him against the evil influences of the materialistic world around him and sowed in him the seeds of the Nivritti life which he joyously nurtured until, as later events proved, it blossomed into sainthood.

His elementary education began at Mangalore. In 1932 he joined the Muthiah Chetty School in Madras where he distinguished himself as a brilliant student. His cheerful personality, exemplary conduct and extraordinary traits earned for him a distinct place in the hearts of all teachers and students with whom he came into contact.

In 1936, he was admitted to Loyola College, whose portals admit only the most brilliant among students. In 1938 he emerged with the degree of Bachelor of Arts. This period of studentship at a predominantly Christian College was significant. The glorious ideal of Lord Jesus, the Apostles and the other Christian saints had found in his heart a synthesis with all that is best and noble in the Hindu culture. To him study of the Bible was no mere routine; it was the living of God; just as living and real as the words of the Vedas, the Upanishads, and the Bhagavad Gita. His innate breadth of vision enabled him to see Jesus in Krishna, not Jesus instead of Krishna. He was as much an adorer of Jesus Christ as he was of Lord Vishnu.

The family was noted for its high code of conduct and this was infused into his life. Charity and service were the glorious ingrained virtues of the members of the family. These virtues found an embodiment in Sridhar Rao. He discovered ways and means of manifesting them. None who sought his help was sent away without it. He gave freely to the needy.

Service to the lepers became his ideal. He would build them huts on the vast lawns of his home and look after them as though they were deities. Later, after he joined the Ashram, this early trait found complete and free expression where even the best among men would seldom venture into this great realm of divine love, based upon the supreme wisdom that All is one. Patients from the neighbourhood, suffering from the worst kinds of diseases came to him. To Chidanandaji the patient was none other than Lord Narayana Himself. He served Him with a tender love and compassion. The very movement of his hand portrayed him as worshipping the living Lord Narayana. Nothing would keep him from bringing comfort to the suffering inmates of the Ashram, no matter the urgency of other engagements at the time.

Service, especially of the sick, often brought out the fact that he had no idea of his own separate existence as an individual. It seemed as if his body clung loosely to a soul which he fully awakened to the realisation that It dwelt in all.

Nor was all this service confined to human beings. Birds and animals claimed his attention as much as, if not more than, human beings. He understood their language of suffering. His service of a sick dog evoked the admiration of Gurudev. He would raise his finger in grim admonition when he saw anyone practising cruelty to dumb animals in his presence.

His deep and abiding interest in the welfare of lepers had earned for him the confidence and admiration of the Government authorities when he was elected to the Leper Welfare Association, constituted by the State–at first Vice-Chairman and later Chairman of the Muni-ki-Reti Notified Area Committee.

Quite early in life, he although born in a wealthy family, shunned the pleasures of the world to devote himself to seclusion and contemplation. In the matter of study it was the spiritual books which appealed to him more than college books. Even while he was at the College, lesson-books had to take second place to spiritual books. The works of Sri Ramakrishna, Swami Vivekananda and Gurudev took precedence over all others. He shared his knowledge with others so much so that he virtually became the Guru of the household and the neighbourhood to whom he would talk of honesty, love, purity, service and devotion to God. He would exhort them to perform Japa of Sri Rama. While still in his twenties he began initiating youngsters into this great Rama Taraka Mantra. He was an ardent admirer of Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda. He visited the ‘Math’ at Madras regularly and participated in the service there. Swami Vivekananda’s call for renunciation resounded within his pure heart. He ever thirsted for the Darshan of saints and Sadhus visiting the metropolis.

In June 1936, he disappeared from home and after a vigorous search by his parents, he was found in the secluded Ashram of a holy sage some miles from the sacred mountain shrine of Tirupati. He returned home after some persuasion. This temporary separation was but a preparation for the final parting from the world of attachments to family, friends and possessions. While at home his heart dwelt in the silent forests of spiritual thoughts, beating in tune with the eternal Pranava-Nada of the Jnana Ganga within himself. The seven years at home following his return from Tirupati were marked by seclusion, service, intense study of spiritual literature, self-restraint, control of senses, simplicity in food and dress, abandonment of all comforts and practice of austerities which would augment his inner spiritual power.

The final decision came in 1943. He was already in correspondence with Sri Swami Sivananda of Rishikesh. He obtained Swamiji’s permission to join the Ashram.

On arrival at the Ashram, he naturally took charge of the dispensary. He became the man with the healing hand. The growing reputation of his divine healing hand attracted a rush of patients to the Sivananda Charitable Dispensary.

Very soon after joining the Ashram, he gave ample evidence of the brightness of his intellect. He delivered lectures, wrote articles for the magazines and gave spiritual instructions to the visitors. When the Yoga-Vedanta Forest University (now known as the Yoga-Vedanta Forest Academy) was established in 1948, Gurudev paid him a fitting tribute by appointing him Vice-Chancellor and Professor of Raja Yoga. During the first year he inspired the students with his brilliant exposition of Maharshi Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras.

It was also in the first year of his stay at the Ashram that he wrote his magnum opus–“Light-Fountain”, an immortal biography of Sivananda of which Gurudev once remarked: “Sivananda will pass away, but ‘Light-Fountain’ will live.”

In spite of his multifarious activities and intense Sadhana, he founded under the guidance of Gurudev, the Yoga Museum in 1947, in which the entire philosophy of Vedanta and all the processes of Yoga Sadhana are depicted in the form of pictures and illustrations.

Towards the end of 1948, Gurudev nominated him as General Secretary of the Divine Life Society. The great responsibility of the organisation of the Society then fell on his shoulders. From that moment he spiritualised all its activities by his presence, counsel and wise leadership. He exhorted all to raise their consciousness to the level of the Divine.

On Guru Purnima day, 10th July 1949, he was initiated into the holy order of Sannyasa by His Holiness Swami Sivanandaji Maharaj, as Swami Chidananda, a name which connotes, “One who is in the highest consciousness and bliss.”

Apart from his distinction as an able organiser of Divine Life Society Branches in several parts of India, his contribution to the success of the epochal All-India Tour of Gurudev in 1950 is memorable. Together they attracted to the Divine Life movement great political and social leaders in India, high-ranking Government officials and rulers of Indian States.

In November 1959 Swami Chidananda embarked on an extensive tour of America, being sent by Gurudev as his personal representative to radiate the message of Divine Life in the New World. He was hailed by the Americans as the Yogi of India very well fitted to interpret Indian Yoga to the occidental mind. He also toured several countries in South America and preached in Montevideo and Buenos Aires etc. From America he made a quick tour of Europe, returning to the Ashram in March 1962.

In April 1962 he set out on a pilgrimage to South India where he visited temples and other holy places and delivered soul-stirring lectures. He returned from the South in early July 1963, about ten days before the Mahasamadhi of Sri Gurudev, a fact which he described as nothing short of a miracle.

In August 1963 he was elected as President of the Divine Life Society. After the election, he strove hard to hold aloft the banner of Tyaga (renunciation), Seva (dedicated service), Prem (love of humanity) and Adhyatmikata (Spiritual idealism) not only within the set-up of the widespread Organisation of the Society, but in the hearts of countless seekers throughout the world, who were all too eager to seek his advice, help and guidance. He has endeared himself to one and all by his exemplary life of a towering Sannyasin, a spiritual magnet and working hard in all directions, for a resuscitation of the glorious Ideals of Divine Life in the world. His carefully guarded personality of an intrinsically good and loving nature of spontaneous servicefulness had brought immense solace in the lives of hundreds and thousands. In addition to his regular tours in this country far and near, the Swamiji toured Malaysia and Hong Kong and scattered broadcast the seeds of true culture, spirituality and the spirit of self-effacement in all actions, thus planting the art of divine living in the minds of thousands of people, which has evoked a deep sense of gratefulness to him in all quarters.

INTRODUCTION

I

“Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime.”

–Longfellow.

The life and actions of a great man–an illumined soul–are ever a permanent fount of inspiration and refreshment to the struggling wayfarer on the hard and weary road of life. The day-to-day activities and talks of such saints and seers form as it were so many instructive and eminently helpful pages of a guide and ready-reference book to bewildered travellers. When the frail raft of life, adrift on the dark ocean of earthly existence, is heaved about on the surging swell of mighty Maya and is tossed by the violent winds of passions and the pairs, the living records of a great life, nobly and intensely lived, act as the benign beams from a brilliant beacon-light brightening the benighted mariner’s way and bringing strength and solace to the solitary sailor on the stormy seas of Samsar…..The conduct of an ideal life faithfully recorded is therefore of the utmost importance to struggling humanity. It is a valuable asset in its fight against the forces of darkness and evil, and is of inestimable help in the perpetual endeavour to solve the numerous painful problems that perplex it on the path of progress towards perfection. In its power to awaken and inspire, in the practical example that it puts before the aspiring one, in its ability to evoke that which is noble, sublime and divine in man and influence him to emulate such an ideal, in these lie the worth and value of such a narration. Such indeed is the purpose of this chronicle, dear reader, and to that degree of the eagerness and receptivity with which you approach it, will inspiration, guidance and strength be thine.

But is there indeed such a pressing need and demand for light and guidance? Comes the query. Ah! Reader, do but open thy eyes and cast a glance on humanity around thee. Therein lies the answer to the query. Everywhere you see mankind in a feverish quest after happiness, rushing after fleeting phenomena and trying to grasp the transitory trifles that go to make up this sense-world. The being does not know what constitutes real happiness or wherein it lies. Neither is he certain how to set about to acquire it. It is all a feverish groping in the darkness, a groping made even more confusing by a hundred conflicting theories, cults, philosophies and ideals that have obscured the mental horizon of the present-day world. Each asserts its infallibility and warns the already-tormented traveller to beware of the other paths. So everywhere there is the cry for guidance, direction and light. Whither lies the way to joy and what direction to follow is the question on every lip. At this juncture comes to mind the sound counsel of the ancient sage Vyasa on Ekadasi Tattva:

Srutir-vibhinna smritayopi bhinnah

Tatha muneenam matayopi bhinnah

Dharmasya tattvam nihitam guhayam

Mahajano yena gatah sa panthah.

“The Srutis are conflicting, the Smritis too differ. Even so, the opinions of sages too vary. The inner truth of what is Dharma is concealed as it were in a cavern. The path to follow is therefore that path which the saints have traversed, i.e., the way to live is even as the great ones lived their life.”

Sound counsel is this, for confused mankind to abide by. And here mark, with these great ones, to whichever age, clime and clan they belong, the basic qualities of head and heart, the sublime impulses that animated their lives, you will find to be everywhere similar.

And to enable you, dear reader, to get to know how one such ideal life has been and is being lived, how it reacted to certain circumstances, what sublime considerations motivated many of its apparently insignificant actions, what noble impulses lay hid behind certain acts that outwardly seemed sometimes ungenteel, nay even crude, these enlightening fragments are presented here as and when they became known to the humble narrator.

They reveal aspects of a life fully, nobly and energetically lived; a life whose chief joy consists in giving itself away ceaselessly to others, to the world at large, day and night, physically, mentally, intellectually and spiritually in every conceivable form and way it can think about. Not being satisfied with this perpetual self-sacrificing, it ever tries to devise fresher and newer ways and means each day, by which to be of some service to every creature on earth, to reach and relieve even the least one on earth. For herein indeed is the secret of all happiness, all joy, in wearing away oneself in selfless and loving service. Life is for joyous sacrifice, not to rust in repose and lethargy.

And behind this reckless extravagance of life, there is withal a deep and silent undercurrent of ever awake spiritual awareness that continuously feels the presence of a universal power and love and knows that it is that power, that love, which flows into and works through him. This fills his life with a child-like artless humility that cannot be understood easily by an onlooker. A unique spontaneity, a complete absence of all artifice or guile, and a complete disinterestedness, freedom from attachment, all have originated from this inner awareness. Such is the life, the living light from which a humble attempt has been made to absorb a few rays and refract them through the prism of the writer’s plainly unworthy and all too inadequate understanding, so that perchance some one may find his path brightened, and his heart lightened and enabled to march straight and vigorously on the highway of life. To chase out darkness and dispel doubts everyone will find this of greatest positive help.

The personality I have had the great good fortune and privilege to move with is, as it were the flower in full bloom, whose budding and growth can be traced far back to his early years at a time when he toiled as a doctor in a hospital in the F.M.S. Those were the days of silent shaping and growth, when for nearly a decade, he strove intensely for the alleviation of human suffering. The fiery and abundant energy of the choicest years of his youth (a period when most of us would like to enjoy for ourselves the best of life’s gaieties) he ungrudgingly and freely utilised in working for the welfare of his fellow-beings around him. He has always been reluctant to make any mention of his early activities and even now is apt to be reticent in divulging his silent acts of everyday service and love. It was by tactful persuasion and opportune enquiry that we could draw him out of his self-imposed reticence and make him tell us something about his life now and then. Finally it was by touching upon a soft spot in his nature that many factors were brought to light. It happened this way. As seekers on the spiritual path we were now and again faced with various problems that agitated and troubled us greatly. Also a great many aspirants were constantly writing numerous letters to Swamiji putting before him their difficulties and desiring help and guidance. Emboldened by this state of affairs we importuned him greatly to tell us how he dealt with similar conditions when he was striving in his early days, what the secret of his success was, wherein lay the source of that bubbling energy and joy, what now animated him every moment of his life and were manifest in every act of his life which would be of help to us and the world at large, by their inspiring example. We pressed home the point that such information would be of immense help and guidance to one and all by the ideal of conduct thus represented by the principle that motivated them and the moral they revealed. We would be the losers, we told him, if information of such practical utility were withheld out of personal disinclination. For the benefit of others he must speak. We urged. And thus we got him to lift part of the veil that covered the intense activity of his life.

II

The holy sage and saint Sri Swami Sivanandaji of Rishikesh, Himalayas, became widely well-known throughout the modern spiritual world. During the past fifty years of this 20th century, he is regarded as one of the world teachers of our times and a great spiritual Master who brought about spiritual awakening into the hearts of millions of people in numerous countries of the world. He became familiar to countless grateful seekers all over the world as a benign Teacher, a great Sadguru and a gracious and compassionate saint who brought spiritual light and guidance as well as solace, comfort and peace into the hearts of innumerable people in different walks of life. His gracious and radiant personality shining with radiance of Goodness, Selflessness and Universal Love attracted earnest aspirants and devotees from all parts of the modern world even as the full-blown lotus flower attracts bees from all the ten directions to his beautiful spiritual abode on the bank of the sacred river Ganga near holy Rishikesh. His entire life was totally consecrated to a continuous spiritual ministry that kept Him engaged day and night in teaching, instructing, training, inspiring, guiding, encouraging, consoling, helping and transforming seekers, spiritual aspirants, Sadhakas and people of all sorts, men and women, young as well as old including students, teachers, professional people and even politicians. Engaged in this ceaseless spiritual work, Swami Sivanandaji shed His mortal coil on the 14th of July, 1963 and merged in the Divine.

This holy saint of modern India was the Light of the East and a Light for the whole world. His country recognises Him as one among the foremost spiritual leaders born in this land of sages, saints, holy men and monks. His life-long services for the revival of the Vedic Religion and the effective propagation of the spiritual science of Yoga and Vedanta have been unparalleled and outstanding in this present century. His name is known in countless homes and has become a byword for spiritual world and ideal conduct and selfless service. Swami Sivanandaji preached selfless service to mankind, devotion to and worship of God, practice of meditation and attainment of Divine wisdom and liberation through the Realisation of Self. He enjoined upon all the principles of TRUTH, CHASTITY and NON-INJURY. Such a life of Truth, Purity and Love and of Service, Devotion, Meditation and Realisation, Swamiji termed as Divine Life. He broadcast His message of Divine Life through His Institution, the Divine Life Society, which he founded in I936. He came to be hailed as the prophet of Divine Life.

In this little book, “LIGHT-FOUNTAIN”, an attempt is made to take a close look into the daily life of this great spiritual luminary as well as to have a glimpse into the background of His early years in distant Malaysia when as a doctor he strove tirelessly to serve, relieve and treat the suffering and sick in the Far East. This book comprises a study of His noble personality with a humble aim to learn about the secrets of His self-development, inner unfoldment and spiritual perfection through the pattern of Divine living, He adopted for Himself. Thus it would become a source of light to us all who also wish to live an ideal life and tread the path that leads to Divine Perfection. This book was written in the year 1943-44 while the spiritual hero and worshipful subject of this study was gloriously alive and full of vibrant and dynamic spiritual service of one and all. Hence, the difference in the present tense is found throughout the book.

May Gurudev’s Grace be upon all seekers and spiritual aspirants who study this book with faith, devotion and with receptivity and reverence. May all aspirants reach the highest spiritual Realisation and attain Supreme spiritual blessedness and Divine Bliss.

OM NAMO BHAGAVATE SIVANANDAYA.

Swami Chidananda

CHAPTER ONE

Days Of The Acorn

Far back, during those days of medical practice at Malaya, the young Dr. Kuppuswamy was the biblical Samaritan carried to the degree of perfection. He effaced himself. His energy, his talents and his body, he did not consider as belonging to him. He belonged to any creature that was in distress and in need of him. He would not spare himself. It happened once that a humble woman of the low caste–a pariah (untouchable)–was about to be of child. She had none to call her own and to be of help. This young doctor, a Brahmin of a most celebrated family was at once by her side, all tenderness and sympathy, more solicitous than if she were his own sister. He looked to her comforts, eased her as best as he could and, as the necessity arose, kept vigil that night, stretching himself down on the earth and passing the night thus outside the door of her lowly dwelling. Only when the task on hand was concluded did he return home and think of himself. It is this inherent thirst to befriend all, to relieve pain, to lessen sorrow, to console and comfort, that animates his life. A genuine disinterestedness and depth of sympathy form leading traits in this personality. It is this rare virtue that constitutes the central secret of the happiness that fills his life. Man forgets his ‘self’ in an all-absorbing love and sympathy for others!

Readers who are acquainted with the life of that saintly man, Dr. Rangachari of Madras, will recall how this sympathy and love formed the key-note of his beautiful life. More than as a famed surgeon of almost international repute, he is enshrined in the grateful hearts of thousands as the man of compassion, who was ever ready to lovingly minister even unto the most lowly. Instances have been when, forgetting all engagements, he had stopped on the wayside and alighted from his car; to be by the side and attend to some destitute low-caste woman who was in labour. Not infrequently, after treating and tending some penurious patients in his nursing home for several days, he refused the small fee they hesitatingly tried to offer him. Instead, he would force them to accept double the amount from him for their diet, etc., and send them away silencing ail their remonstrances.

Even so, Swamiji, while at Malaya, would keep poor patients in his house, nurse them back to health and send them after giving them some gift out of his own pocket. Without the least aversion he would tenderly support untouchable patients on his lap, clean their beds and even dirt cheerfully, in case they were too weak to move.

But one point we may note here with profit. Though having the softest of hearts, brimming with an almost motherly tenderness, gentle to a degree, yet these essentially feminine traits did not at all make him effeminate and timid or weak-willed. On the other hand, with all the woman’s sympathy, concern, desire to comfort that had in it something of the passionate and inspired urge of a Florence Nightingale, Swamiji was a purposeful and enterprising man. He lived a manly life, very active and vigorous. He was the soul and centre of all popular functions and social gatherings which he animated with his cheerful and ready activity. If there was any trouble at the hospital, any discontentment among the employees–a threat of strike–it was the young doctor who had to be on the spot to set it right at once. Even a perfect stranger to the town happening to come to the young doctor’s notice, immediately had all his problems solved. Whatever he wanted, was arranged by the eager host even before he expressed them, right up to the moment of his departure when the doctor would personally give him a send-off.

He also took a keen interest in sports, followed important tournaments, wrote articles to papers, like the ‘Malay Times’, etc. He was the author of several instructive tracts on medicine, hygiene, etc. He was editing a medical journal too.

If only the youth of today are fired with this genuine zeal to serve and to relieve suffering, sorrow will vanish from their lives and the earth will become a blessed place filled with joy.

Years later, when Swamiji, no longer a fashionable doctor but a monk given to intense asceticism and Sadhana, was in seclusion at Rishikesh, the self-same flame continued to burn steadily within him with the same warmth of compassion and desire to serve, with which his heart was aglow in the earlier days. To him, turning away from worldly pursuits on a higher quest did not mean the suppression of the sublime sentiments and the extinction of the elevating emotions that were his inherent nature. Rather they became the more intensified and refined by the touch of a higher unselfishness and wider consciousness.

We have here an incident that reveals some striking aspects of this strange personality. Even after renunciation he made it a practice to help the pilgrims to Badri with medicines. The road was very bad and the journey difficult and attended with several risks. Therefore he used to distribute packets containing seven or eight medicines to the pilgrims he came into contact with.

It happened on an occasion that a Badri Yatri came to see him one evening. After a short talk when he was taking his departure Swamiji gave him the wonted packet with the directions for using the medicines. The Yatri left for Lakshman Jhula, the next halt. Anyone would have retired and slept restfully that night pleased with his work, for as the good old saying goes, “Something attempted, something done has earned a night’s repose.” Not so Swamiji. After the visitor has left, it occurred to Swamiji that he should have given a certain special medicine that would be particularly helpful to the pilgrim. The thought filled his mind that he had not done the utmost, the best that he could have done. So, very early the next morning, even before dawn, he took the medicine and started at a steady uphill-run to catch up with the traveller. When he reached the next halt, he found that the pilgrim was an even earlier riser and had already proceeded on his way. Nothing daunted, Swamiji at once commenced running higher up to Garud Chutty only to be informed that his quarry had passed higher up. Undismayed, the pursuer pressed on to Phul Chutty and not finding him even there ran further up, caught up with, the pilgrim near the 5th mile and there gave him the precious medicine. By this time it was past nine o’clock and the monk had to race back to his Kutir to be in time for the daily alms at the Annakshetra.

Let us pause and reflect for a moment what this one incident reveals to us. We see that it was all done silently and unostentatiously, none else being the wiser for it save the two concerned. All for the sake of a person whom Swamiji had never seen before nor perhaps afterwards. He would not be satisfied by doing a little but must give his very best. The urge in him has always been to do the maximum good. A task undertaken must be pursued to its logical conclusion and done perfectly. Such was the genuine aspiration in him to serve, that to the winds went all considerations of personal comfort and even daily spiritual routine. Overcoming physical laziness (the greatest bar and pitfall to the selfless worker) to have run nearly 6 miles distance, gives an idea of the absolute, almost breath-taking sincerity and wholeheartedness that burns throughout the whole act. Ordinarily, a person after going up a little distance and failing to catch up with the pilgrim would have returned succumbing to a sense of moral satisfaction of having done his duty. The whole incident bespeaks the high mettle that made up his personality.

At another time, an old lady rashly undertook the difficult ascent to the shrine Nilakanth Mahadev, about 7 miles from Swargashram. The strain proved too much for her and on her return both her legs got swollen. Without hesitation Swamiji went to her aid and set about shampooing her legs until relief was obtained.

On several occasions, he gave up even his Sadhana and Tapas to be by the side of a sick man until the latter was nursed back to health. When a junior monk, the Swami Atmananda, lay dangerously ill at Rishikesh, Swamiji left Swargashram at once and came over to Rishikesh (where he put up for nearly three weeks) and nursed him successfully through a critical period.

The grateful monk recently wrote, “He whom I have the honour to call Gurudev, stayed during my severe sickness, in some neighbouring Dharmashala at Rishikesh for about twenty days to personally attend to me. He saved me when my life was in danger during that illness.” A European Sadhu, a disciple of Shree Meher Baba, used to tell Swamiji that whenever the latter approached his sick-bed he felt healing vibrations and obtained relief at once. Indeed, genuine and disinterested love cannot but make itself felt as a positive force emanating from the fortunate possessor. A similar love it was that irresistibly drew the hearts of those that approached the Lord Jesus Christ and the Lord Buddha and in our own times, the patriot saint Gandhiji–the Mahatmaji of the adoring masses.

The modern boy-scout is urged to do at least one good turn every day. Swamiji’s persistent insistence to everyone he meets, is to fill the entire day from dawn to dusk with good turns. At all places, in every situation, throughout the waking hours, ‘service’ is to be the motto.

A robust positivism characterises Swamiji’s attitude towards this factor of being useful and doing good. “Ever be on the lookout for an opportunity to serve. Never let by even a stray chance of being of some service. You must be like a watch-dog, alert and keen to grasp at once any possibility that presents itself, of being useful. Sharply watch and see what help you can do to those about you”. Thus run some of his favourite admonitions to eager workers. Nay, he went a step further. You must create opportunities to do something for others. Do not keep quiet waiting for a chance but create means of making yourself useful and helpful, whichever way you are particularly suited by temperament, talents and natural disposition.

No one is to neglect his or her natural talent. If a person is endowed with fine physique and is of an energetic disposition, let him learn some Asanas and exercises and spread physical culture among students and youths. Let him do active and intense social service. A doctor should treat the poor gratis. He must treat his patients with gentleness and kindliness. Let him also be scrupulously honest in all his dealings with his patients. A lawyer should refuse to argue false cases and avoid taking recourse to untruth on any account. This will constitute the greatest service to the cause of ‘justice’ in his capacity as lawyer. In the educational field let the teacher or professor throw himself heart and soul in elevating and moulding the character of the students entrusted to his care. A trader, by being honest in all his transactions, renders his service to society. Even a menial servant should faithfully do his routine duties, looking upon his master with loyalty and reverence. Thus, to suit every case, each in his particular sphere could live up to this ideal of being helpful and serviceable.

As with Browning, Swamiji too firmly believes that “All service ranks the same with God.” There is no act of service ever so trifling that one would be justified in passing it by. For it is not what we do that matters, but with what attitude it is done that counts. Let every act be a beautiful blossom reverentially laid at the feet of the Divine, manifest as Humanity, i.e., Virat. And I have found that with Swamiji this ‘worship by service’ is not so much poetry but it is the very fact of his being.

Coming across old Sadhus, long-standing residents of Rishikesh and its environs, I would sometimes obtain glimpses of Swamiji’s Swargashram days in the course of my talks with them. From what I could gather in this way, I saw that Swamiji’s method of service had one valuable feature which is worth noting and emulating. That is the quality of motivelessness and absence of ostentation. They would relate how Swamiji would wait for the time when they were away from their cell, either at toilet or bath, then enter it, sweep and clean the floor, wash the pot and refill it with fresh water and come away silently. At other times, if a recluse happened to be ailing, Swamiji would himself go to the Kshetra and get Bhiksha on behalf of the sick person and procuring a little extra milk would place it in his room and come away.

This silent and humble service was not that of a devout youngster to his elders (for one must remember that at the time Swamiji was nearing his fortieth year–a time when a person usually becomes invested with a sense of dignity and subtle egotism peculiar to middle age). This was possible because Swamiji has, throughout his life, unconsciously retained the essential simplicity of the child.

When a certain monk belonging to the well-known Ramakrishna Order, Swami Tanmayananda by name, was once laid up with a severe attack of pox, Swamiji attended upon him for two or three weeks incessantly doing all the work of nursing, feeding, cleaning and fetching pots full of water from the river. Years later when recently I chanced upon the monk Sri Tanmayananda, now grown old and infirm, he feelingly related to me this incident and said, “He saved me from certain death that time. None could have possibly served me in such a way as he did. If you see him please take a note from me.” And I wrote on a piece of soiled paper his message of informal greetings to Swamiji, familiar in the way of long-standing friends and gratefully reminiscent of the old days.

The test of genuineness of the selfless server is the whole-heartedness of the urge in him. He must have no vestige of any sort of mental reservation in his action. Else it will at once be felt by sensitive natures and they will shrink from accepting the proffered hand. There was at that time (about 1926) a young anchorite practising austerities at Swargashram. He belonged to a very highly-placed family of the Southern Provinces, almost a prince in a small way. So complete was his renunciation, so severe the standard of self-denial, that he had set up for himself and so extremely sensitive his disposition that he not only never accepted any sort of gift from any one but also scrupulously avoided even borrowing anything. He persistently declined Swamiji’s offers of little things of simple everyday necessity and would not allow of his attempts at small services even. But gradually the absolute selflessness and the genuineness of the desire to help, of Swamiji so overcame him that, he ended by accepting whatever Swamiji brought to him. The onslaught of this disinterested love made Bhaskarananda (for that was the name of the youthful ascetic) relax the stern austerity for which his name had become a byword amongst the hermit community of the place.

But not unfrequently the situation was of a different kind. Hearing of his efficiency as a man of medicine and his loving nature numerous people would invade his cell for help and treatment at all odd hours of the day. So much so, that at times he felt forced to flee the locality and hide himself either among the huge rocks by the waters’ edge or in some dilapidated Kutir further inside the jungle. Thus he would snatch a quiet hour or two for deep meditation.

At times urgent summons would come from some distressed person; then leaving aside everything Swamiji would run (at times even at midnight) to relieve him. Once an amusing incident occurred which proved a trial to his patience. A fastidious Sadhu at midnight invaded his Kutir, even climbing the protective fencing surrounding it, to hammer on the door insistently. It was to remove some grit that had entered his eye. Though sorely tried, Swamiji maintained his equanimity, carefully attended to his night-raider and sent him back satisfied. Calls to treat scorpion-bite would come at all unexpected moments because the creatures abound in the locality even to this day. Not once did he allow his temper to be ruffled even under the most annoying circumstances. Such then is to be the true spirit of the selfless server. Let him aim to be cheerful and keep alive a genuine enthusiasm, not allowing disgust to creep in even unnoticed–an ideal to be kept in mind, be it by the student, the boy-scout, an occasional volunteer or the member of some service league, in private or public capacity.

Once or twice these interesting remarks have escaped him… “On rare occasions you must even be aggressive in your service. Sometimes helpless persons in need of aid will foolishly refuse aid. In such cases do them the required service in spite of their hesitation.” He would laughingly cite two occasions when he employed such aggressive methods, once forcibly carrying about the monk Jnanananda in the hospital at Lucknow where he was undergoing treatment; unable to walk the daily round from the ward to the dressing-room and back again, the monk was at the same time unwilling to ride on Swamiji’s obliging shoulders. But the latter took the matter into his own hands and carried the protesting but grateful monk on his back daily.

The second incident was how he turned a deaf ear to the remonstrations of the venerable lady, the pious and devoted Rani of Singhai and himself lifted her up from the ferry-boat on to the steamer as they were proceeding in a party on pilgrimage to Ganga-sagar. The water was rough and the boat heaving alarmingly, and the frightened ‘dear old lady’ (she was about seventy then) was in a quandary. She was at the same time full with the instinctive feminine reluctance to accept Swamiji’s aid. But the latter did not waste time to argue. In a trice the protesting Rani found herself gently and reverentially lifted up and safely deposited on board the steamer, good-naturedly riled by her own daughters laughing merrily at Swamiji’s effective tactics. “But”, (I remember his adding quietly) “at all times be uniformly decent, delicate and courteous. Always have consideration for others’ feelings. Never be rough in the name of ‘service’.”

CHAPTER TWO

The Apostle Of Prayer

To such of us that are so placed in life as to be denied the opportunity and scope for doing actual active service most of the time, there is another, a little known aspect of Swamiji’s life, which has a wealth of significance and inspiration. That is his practice of a continuous, silent prayer, the hidden habit of ‘constantly willing good’ to all. Those who are unable to engage in sustained service let them pray for everyone, at all times, everywhere and on all occasions. Let them commence to earnestly wish the happiness and good of all creatures. To fill the heart with sincere motiveless love for all will, by itself, mysteriously help those in need of aid and relief. This will itself constitute a sublime service. Service is ‘Love’ in expression and the cherishing of such a broad love in oneself, coupled with a strong positive desire for Universal weal, becomes an effective and higher sort of service. By generating a current of helpful and healing vibration, it will contribute to common welfare in a subtle but none-the-less powerful way.

Swamiji puts this into practice everyday, even now. I have observed that there is no exception to the prayer that he says. If he sees a sick person he at once breathes a prayer to him. Happening to read the obituary report of some person he will at once pray for his peace. For the war to end soon as also for the relief of the starving multitudes in Bengal, he regularly offers daily prayers. Seeing a lame dog, a prayer will rise up in his heart. Perhaps an ant is accidentally trodden underfoot in his presence, at that very moment a feeling heart would melt in hidden prayer all unnoticed by those about him. Even hearing from another that someone else is ill makes Swamiji pray for the stranger’s recovery and health. Perhaps some little disagreement resulted in a momentary angry word or two between a couple of his own students; then too Swamiji’s only reaction would be to silently forego his next meal and pray for the erring worker. Thus firmly has this habit of prayer become grounded in his nature that it has come to be an inseparable part of Swamiji’s very existence.

There is something so peculiarly and essentially Christian about this trait in him that the ordinary non-Christian will fail to understand him. One may find it somewhat difficult to appreciate the significance of this habit which savours so much of the Occident. The devout Christian on the other hand will find it to be quite in sympathy with his firm beliefs. Swamiji himself is very emphatic in his convictions about the efficacy of prayer that is really earnest and genuine. He once said in reply to a query, “Yes. Prayer has tremendous influence. It can work anything provided you are sincere. It is at once heard and responded to. Do it in the daily struggle of life and realise for yourself its high efficacy. Pray in any way you like. Become as simple as a child. Have no cunningness or crookedness. Then you will get everything.”

That he has proved this to himself in his very life, I have no doubt. I had the fortunate privilege to freely go through the voluminous mail that he daily receives, practically from throughout the length and breadth of the land. Without the least exaggeration I can state that people keep writing to him from the whole of India. I found that everyday there are numerous letters begging Swamiji to pray for some person or other. Sometimes it is a prayer for recovery from illness. At another it is for the long life of a new-born or the prosperity and happiness of a newly-wed couple. One will write for prayer to succeed in some critical endeavour. Then grateful acknowledgements of the mysterious efficacy of Swamiji’s prayers come as unsought-for testimonials. Call this a result of subjective faith, law of psycho-therapeutics or what you will. The bare truth is that it is a matter of fact. Quite recently the mail brought with it three urgent telegrams on three consecutive days, all requesting for the prayers of Swamiji on behalf of a chronic sufferer, one Gopal M. from distant Feroke in Malabar. This and numerous similar instances make one pause before venturing to entertain any doubt or scepticism as to whether Swamiji’s firm opinion on the subject of prayer is based upon personal experiment and experience or not. The intellectual and the rationalist is bound to smile indulgently at this somewhat eccentric anachronism of such a kind of perpetual piecemeal praying, for anything and everything, in an enlightened age as this. But one would do well to ask himself how it is that Sri Gandhiji, universally acknowledged as one of the greatest thinkers of our times, happens at the same time to be a staunch and confirmed votary and a most ardent advocate of prayer? Were the practice of prayer an obsolete antiquity, then Gandhiji’s critical intellect (whose pre-eminence none questions) would have ere now rejected it unhesitatingly. Those who regard prayer as something queer and puerile are those who have never bestowed a thought as to what prayer is and how it works. Prayer for others is, in a way, the intense willing of good. Now this constant habit of unselfishly desiring good to all evokes a stream of pure ‘love’ in the praying heart. Pure unselfish ‘love’ is in essence really God Himself. Love is the very essence of divinity. Thus in prayer a wave of divinity is set up in the etheric field in which the Universe has its being. And wherever there is need of it, this wave reaches and acts with its benign force. When one reminds oneself that right at this very moment some insignificant individual (let us call X) sitting at a table in a dingy office in one corner of the world, is able by jabbing away at a knob with a staccato rattle, to register a message and set things moving thousands of miles away in some other corner, then it becomes easy to accept that there can be a positive efficacy and power in prayer. The mental and supra-mental powers in man are rapidly being recognised as most potent factors in the shaping of human affairs.

Swamiji is so filled with this conviction that any observer, who is curious enough to note, will find that he has tagged up prayer as an invariable item in every sort of occasion and function imaginable. I could see that whatever is done, either by himself or by others under his guidance, always started with and ended with a prayer. If a room was being constructed then the workers were made to gather round a tiny lamp, sing the Lord’s Name, chant a prayer and then commence the work. A consignment of marble image arrives and immediately a prayer is arranged. Should a dinner be given to a party of Sadhus, then too, a prayer is an invariable item of the function. While packets and leaflets are done up or magazines wrapped for mailing, Swamiji would tell the workers “Pray and praise the Lord while your hands are doing the work. Do not carry on loose talk.” And at the Ashram itself, he and his little band of workers, assemble in the prayer hall on the hillside and there the Lord’s Name is chanted in unison and then a prayer for Universal Peace is solemnly uttered in the stillness of twilight.

CHAPTER THREE

Being And Doing

To the casual observer, however, externally there is very little in Swamiji’s day-to-day activities to suggest a man of prayer. Indeed the exact opposite impression. If ever a person is thoroughly removed from the dreamy mystic type, it is Swamiji. For I have seldom witnessed a busier or a more intensely active life. For an ascetic, who had shut himself up in seclusion for more than half a decade and has stuck to the selfsame spot for well nigh a quarter of a century, he is of an incredibly dynamic type. I have to admit that, when I was new to him, until I got accustomed to his surprisingly ceaseless activity, I was for sometime left helpless and gaping. Recently they celebrated his 57th birthday (and six months have already passed) and yet to this day, try as I may, I cannot get over the feeling that he is not one hour older than sixteen. And rest assured, I am not a bit sentimental about this, but from what I see with mine own eyes, I am literally forced to accept this paradoxical fact. There is about him an air of such juvenile vivacity that completely belies his years. Oftentimes it happens that some idea suddenly strikes him or some new scheme unexpectedly appeals to him. It sets him at once all abubbling with an exquisite boyish enthusiasm. His cheeks are set aglow with a childlike excitement and expectancy and the lively sparkle in the clear eyes reflects the keen zest with which he applies himself to anything that once catches his fertile imagination. With him there are no half measures; there is nothing of indecision, much less of hesitation. He is as thorough in his actions as he is earnest and deep in his inward life of prayer and almost constant holy recollection.

From the solemnity and silence of his room by the waters’ edge, a room sounding only with the whispers and murmurs of the sacred river softly flowing past in all her majestic serenity, he will step out in the morning at about ten. The moment he steps out of his room, he is a different man altogether. He becomes a veritable live-wire. With a brisk gait, he will walk up to the Society premises and his appearance is at once a signal to set the little community of his student-workers hum with activity. It is impossible to be dull or slovenly in his presence. His dealing with certain aspirants who used to go about their work in a dreamy and abstract fashion, was rather amusing. One such aspirant had acquired a sort of deceptive indolence imagining it to be a way of expressing inner spiritual tranquillity. It happened that Swamiji was conversing with some visitors on the broad verandah skirting the hall of common worship on the hillside. The youth in question came ambling up the pathway in leisurely stateliness which immediately caught Swamiji’s eye. “Come on here, young man” he called out, and then, “What is the matter with all of you? Are you being underfed? Is there nothing in the kitchen? Or is it that you don’t get time to eat? Your hair is not grey yet. Why then this deportment of a half-starved being? Where is your energy, your youth? Why can’t you step about with a bound and a jump? Let me see you sprint. Now take a run round the hall. Come on.”

A sheepish expression that the youth assumed so tickled Swamiji that he suddenly turned round to me and said with a serious nod, “Look here, I want to send this X (naming the youth) to a military camp. It is only a military training which will infuse pep into these entranced hermits. I think man is born lazy. It seems that a life of renunciation is synonymous with physical quiescence and inactivity. Where they obtain such ideas the Lord alone knows. You have to learn lessons from the busy man of the city and the young medical students. How agile, efficient and full of enthusiasm is the young medico! How briskly from block to block, from ward to ward, along verandahs and through corridors, does the medico step about in his daily work in the hospital! Why can’t we take his example? A world-renouncer should, on the other hand, be the most dynamic of workers because he has the advantage of wholly being free from the multifarious vexing activities and distractions that beset a man in the worldly life. Be energetic from tomorrow. Let me see you run and not walk. Let me see you everywhere at once. Sloth does not constitute sainthood. If it were so, then every chair, table, pillar and wall would have to be canonised. Shake yourself up, my young man, and turn out into a versatile worker”.

This drew forth a hurried and embarrassed “Yes Sir, I will, I will,” from the confused youth as he hastily retreated from the spot. The next instant Swamiji naively addressed the visitors saying, “What do you say to this, am I right in having said so? Or am I being a bore in sermonising? Don’t you really think that everyone ought to be active and energetic?”

And sure enough, from the next day, not only the particular aspirant but also one or two other amblers were observed to step on it with added zest and vigour.

In this connection I cannot help digressing to mention a peculiar phenomenon that has caught my attention. It is this. Whatever Swamiji asks or advises a person to do, sooner or later the person begins to follow in spite of himself. He may be a most heedless and negligent sort. He might forget Swamiji’s suggestion. He may just make light of the instruction, or fail to pay any attention to it, due to preoccupation. But he will invariably end up by following it. Now, what is the explanation of this? The reader doubtless knows that there are thousands of irate fathers, despairing mothers, helpless school-masters and professors, furious employers and bitterly complaining public leaders, all utterly dismayed and distracted at their failure to make others listen to their ceaseless admonitions, obey their words and follow their lead. They are at a loss as to how to make those about them pay any heed to their counsel. But here is one, surrounded by a band of workers (who have by the very nature of their lives, no ultimate connection with one another, and who have freedom from all bonds as their aim) who utters a few sentences of advice and instruction and never racks his brains about ways and means of enforcing them; and yet within a short time beholds them being diligently put into practice. Wherein lies the secret of this? What lesson of practical utility could be drawn out of this? I am forced to conclude that it lies in the deep difference that exists between the mere saying of certain things and actually being and doing them oneself. People are not generally moved to action by the words of a person but, on the other hand, almost unconsciously begin to copy and follow him when they observe him actually living his precepts. If one actually lives the exhortations that he utters, then, even the most recalcitrant and the proudest will bend before him. For, example verily is yet the highest known method of evoking emulation. For instance, what a vast gulf there is between one who professes and preaches selfless service and another who, according to his native disposition, ceaselessly serves all beings with equal vision? Trying to review the serious problem of advice and obedience in this light will doubtless help the vexed parents, preachers, teachers and leaders a great deal.

It is this law that is also at the back of the admirable attainments of the modern miracle of a man, Sri Gandhiji, in the field of politics and social morality. To millions, his is a name to conjure by and he is a power to be reckoned with. This phenomenal achievement is attributable to the utter sincerity of his life and the exact correspondence of his life to the beliefs he holds. To do even the lowliest act as the highest worship is one of the dominant notes of his life. One is told how when his son Sri Devadas Gandhi was married to the daughter of the reputed C.R., the very first thing Gandhiji had them do, immediately after the ceremony, was to take up broom and pail in hand and clean some spots in the locality. This was the wedding present of the groom’s father to the new couple! The ‘Old Man of Sewagram’ has successfully striven to make himself the living embodiment of the ideals that he seeks to propagate.

This very phenomenon it is that shines through the varied activities of the dynamic saint of ‘Ananda Kutir’. It dawned on me that to Swamiji ethical and spiritual truths were not so many sentences on the pages of the sacred books, but were to become facts of one’s life, a life of being and doing. Let one but strive to become the incarnate expression of the advice and admonitions that he wants to be heard and followed, then, as sure as day follows night, will the world follow his lead. To be like the Brahmin in the fable and to expect obedience will only prove futile. It is related that a Brahmin of Karnatak, a reader of scriptures by profession, was on one occasion presented with a basket of vegetables by an appreciative member of the daily audience. There were among others, a few fresh and juicy brinjals in the vegetables presented. The Pundit on reaching home that day handed them to his timid wife and asked her to prepare a nice curry of the brinjals. Now it had so happened that the day previous, the Pundit had discoursed on some texts dealing with the qualities of various things and had explained that brinjals were to be eschewed from one’s menu as they (brinjals) were classed among articles that tended to rouse the dire nature or Tamas in man. His wife who had been present during the exposition had heard this and now she recalled the passages and made bold to mention the injunction to the Pundit. Instantly, he turned round on her and exclaimed, “Hush woman, do you seek to teach me ‘Dharma’? Listen, the vegetable that was forbidden is the ‘brinjal in the book,’ not the ‘vegetables in the basket’. Make haste thou and cook this brinjal in the basket.”

Referring to this type of people, the saint Sri Ramakrishna used, in his own inimitably quaint way, to say, “Mere erudition and knowledge of scriptures is of no avail. If a scholar is also endowed with dispassion and discrimination then I feel nervous while visiting him. But if he is a mere Pundit without Vairagya then I look upon him as a mere dog or a goat.”

It is the fact that, to the best of his ability, Swamiji constantly endeavours to embody in life whatever he speaks and writes, that makes it impossible for one to pass over his words lightly. The practical counsels that come from Swamiji have a vital, though quiet, authority behind them. They carry with them an incontestable assurance and reliability such as that behind a serum that comes out of the Pasteur Institute or a formula given out by ‘May and Bakers’.

CHAPTER FOUR

Secret Of The Intense Activity

When he urges one and all to keep themselves ever active in service and doing of altruistic works, it is just what he is himself actually doing. There is not one idle moment in Swamiji’s life. He does not know what ‘ennui’ is, just as Napoleon did not know what ‘impossible’ meant. At times he would say that “24 hours are all too little for a day. They are not enough. Every moment is precious. Even a single minute should not be wasted. Keeping the body and mind fully engaged is the best panacea for all physical and mental ills. Unregulated living and idleness are prolific parents of every known evil. Therefore, like Benjamin Franklin, Samuel Smiles and others, Swamiji sticks to a time-table of activities for the day, allocating definite occupations for set times of the day. This practice he recommends to all people in whichever walk of life they be. This principle of a definite daily routine, while giving scope for maximum and continued activity, yet enables one to maintain serenity as it eliminates all aimlessness and distractions. Though, by nature, Swamiji is utterly the reverse of all formality and convention, yet there is not the least tinge of weakness or vagueness about him. He combines ceaseless energetic activity with constant and undisturbed serenity. Delightfully unconventional he is, yet effortlessly and unconsciously dignified. This has been possible because there are no ‘loose ends’ in his time and activities. It is the man that does not know “what to do next” that usually ends in failure. The harmonious blend of serenity and activity Swamiji manifests, is the acquisition of a life of carefully regulated action and a full and fixed daily routine. Such exact routine and regularity effectively eliminates all idleness and agitation from the mind, investing life with a mantle of dignity and calm which one can’t dream of finding in the irregular and chaotic life of a man without programme and principle.

Doubtless, time is short and to devote it to worthy pursuits, the busy man of the city finds very little of it to spare. Yet, he will find that if he but regulates his activities, he will, in a short time, discover that a good deal of time which is habitually wasted away unnoticed will come to light. The fruitful living of one’s life is only possible through a wise and worthy utilisation of time. The latter is therefore important indeed, and no effort is too much if thereby one is enabled to lessen sorrow, enhance one’s own as well as others’ happiness in this world. The time that you daily spend on the train, tram or bus, to and from your place of study, work or business, could be harnessed and utilised for self-improvement and evolution instead of in the time-honoured processes of window-gazing or gently dozing. Further, the midday lunch time recess is not to be frittered away flippantly in gossip. Then again, when a man waits for the bus, tonga or train, he invariably gives himself up to profitless worry or to aimless reverie. This twofold evil must be stopped and such time also has to be ‘pressed into service’, if you are really eager to win the battle against all failure, weakness, pain and evil. These odd bits of time, slipping away here and there, all unnoticed, have to be carefully checked up and put to good use. Just as in a total struggle, every unit of man-power is conscripted and also all manner of scrapes is collected and made into weapons of offence and defence, even so, the individual attempting to achieve success must pool together all his resources and utilise every moment of his life-span profitably. Every single day is, as it were, a valuable oyster-shell that comes floating-by on the time-current of the stream of life. The diligent one who realises the great value of time and makes a full and careful use of it has, in effect, promptly opened the shell and secured a priceless pearl ere the oyster has floated away ‘down-stream.’ The waster of time has lost the pearl never to see it again. Day by day through the years, wasted days form so many rings of iron that link themselves into a chain binding the heedless person to the existence. But the profitable life forms, at the close, a beautiful chain of precious pearls laid at the feet of the Giver of life.

Some of those who have come into personal contact with Swamiji have been inspired by his example and have adopted this course of using every moment profitably. There is no doubt that it has changed their lives for the better. A notable example of this is Sri D.N.J. of Delhi, a gentleman of the legal profession, who has successfully cultivated this habit of making the best use of every minute of his time to improve himself. The popular business psychologist, Dale Carnegie too, lays very great stress upon the vital importance of this practice. Assiduously cultivated, it will definitely bring astonishing returns to the seeker of success. One should cultivate the same jealous parsimony with regard to time as displayed by the vigilant individual who exclaimed, “Alas! I have just lost one golden hour set with sixty diamond minutes.”

This great emphasis laid by him on the conservation and profitable utilization of time has resulted in a unique feature, i.e., the Spiritual Diary. It will act as an effective ‘Cerberus’ to keep guard over the elusive factor of ‘Time’ by keeping out the thieves–idleness, aimlessness and procrastination. Referring to the incalculable benefits of maintaining the ‘diary’ Swamiji has stated, “There is no other best friend and faithful teacher or Guru than your diary. It will teach you the value of time. Then you will be able to know how much time you are spending for worthy purposes. If you maintain a daily diary properly, without any fault in any of the items, you will not like to waste a single minute unnecessarily. Then alone you will understand the value of time and how it slips away.”

Like the sped arrow and the spoken word, the spent hour too is irrecoverable. This aspect of it is ever vividly before Swamiji’s mind. We have it in his valuable work “Sure Ways for Success in Life” where he writes, “Time is indeed most precious. It can never come back. It is rolling on with a tremendous speed. When the bell rings, remember you are approaching death. When the clock strikes, bear in mind that one hour is cut off from the span of your life.” Well has the Western mind conceived of ‘Time’ as a fleeting old man with a single tuft of hair on the front of the head. ‘Time and tide’ are two mighty forces that can neither be held up nor recalled for the convenience of man. Therefore with Swamiji the motto is ‘Do It Now.’ What can be done a month hence should be done today. If a thing may be done tomorrow, well, do it now. Things must be done at once. Death will not announce his visit to you beforehand for you to prepare yourself. “Life is short. Time is fleeting. Arise, Awake, Realise the Self”–These are terse maxims which he never fails to present to those that seek his guidance. To one who spoke of ‘turning over a new leaf’ on some date in the near future, Swamiji spiritedly exclaimed, “Don’t say that. That tomorrow is for fools. It will never come. Days, months, years, even life itself, will pass away unawares. Exert yourself from this very second.”

It is a significant thing that Swamiji, a Sannyasin and one revered by many as a bold exponent of Advaita Vedanta should lay such emphasis upon diary, routine, self-culture and success in life, etc., because Maya-Vadins, as a rule, negate the very existence of the body, Vyavaharic activity and the world itself. There is a sound reason behind this. Advaita-Siddhi is actually the highest pinnacle, the grand culmination and the crowning glory of spiritual life. It is the last word in realization for the Vedantin. As such, it is not a matter for glib talk and lofty presumption by all and sundry. One has first to render himself fit to receive and assimilate this dizzy truth by preparing the mind through a life of discipline and regulation. Breaking through the cobwebs of Mayaic illusion is not a joking matter. Every moment of your life, every ray of your mind and every faculty of your being has to be resolutely directed towards the task of freeing yourself from the coils of the narrow egoistic personality. To the earnest seeker, all the difficulties and obstacles are very real indeed. Details of discipline have to be very, very, practical. Theory will only serve to inspire and to guide but practical exertion alone gradually ‘step by step’ turns the theory into fact. As he often says, one has to ascend the ‘Ladder of Yoga’ step by step and in this process, vigilance, conservation of energy, profitable utilization of time, are all of paramount importance.

CHAPTER FIVE

Lessons On Life

It is on the subject of spiritual life and practical spiritual Sadhana, more than on other matters, that a great many lessons could be drawn through the unbiased study of Swamiji from the early stages of severe discipline, asceticism and inner struggle; the steady and determined efforts of the earnest aspirant, the progressive victory of a resolute will and a regulated routine over the deceptive wiles of the mind and finally the full unfoldment of the present personality.

From what could be gathered of his previous life, before he took to this path of renunciation and spiritual attainment, some very instructive facts come to light. In a way his earliest years were the fashioning (though unconscious) of the framework over which the inspiring edifice of his later spiritual life was built up.

From the very beginning, Swamiji had the natural faculty of devoting his entire attention and all his energies to any task that he happened to take in hand. He would ignore and forget everything that did not concern the matter on hand. As an youngster, for instance, at one period in his teens, Swamiji was fired with the idea of physical culture. His mind at once caught up the idea enthusiastically and was filled with it. He immediately began to take keen interest in exercising on the parallel and the horizontal bars. His orthodox parents did not view it with any great favour. But the boy used to be up from bed, even as early as 3.00 a.m. or 3.30 a.m. in the small hours of the morning and slip away before the rest of the household arose from slumber.

“I have to confess,” he once said, with a reminiscent twinkle in his eyes “that many a time I used to place a pillow on my bed and cover it up carefully with a blanket to give the appearance of my innocent self sleeping soundly.” This was for the edification of the watchful father. The boy would at that time be in the gymnasium absorbed in his vigorous pastime.

He was endowed with a fair amount of dash and boldness and consequently to receive august visitors, deliver addresses or enact plays, he was much sought after by his friends and superiors. Though modest, he would readily come forward on occasions and was not to be overawed by personalities. This latter trait is even now prominent in him and it had served him greatly in his Sadhana days at Swargashram. It has also partly helped in making him the frank and fearless reformer that he is. He is not easily subdued by public criticism. He does not care for anyone’s opinion once he sets himself to do something which he is convinced is conducive to common weal.

It might well be within the personal experience of the reader too that, when one tries to stick to his well-grounded convictions and assays to act up to them, he is always confronted with a good deal of active opposition that tries his mettle. On such occasions, Swamiji would never desert his principles. With a characteristic gesture, the right hand pushing up the spectacles and a quick vigorous shake of the index-finger of the upraised left hand, Swamiji once exclaimed, “No! No! I am not always like this. I am most aggressive. If occasion arises, I shall never give in. Sometimes I become a fighter and then I can be formidable. In that respect I am Guru Govind Singh. One has to be spirited when the situation demands.”

This is indeed sound advice for those of us who are striving to live up to certain high ideals and principles and encounter trying situations in the process. Particularly when you are disposed to be quiet and humble by nature and, therefore, prone to relapse into timidity in the face of opposition, the above aspect of Swamiji’s nature affords a clue to the attitude you should adopt.

His days as a student of medicine were also characterised by the same whole-heartedness and zeal as is so evident in him even now. Apropos of a casual remark once made within his heating, Swamiji once said, “I really don’t know what it is to do things by halves. I always used to do everything fully and properly. The usual sort of eleventh hour preparation, so common among you, youths of the present day, was unknown to me. I was ever ready to answer examinations on any subject without previous intimation. Even now, I feel just like a student about to attend an examination. Such a sort of constant readiness and vigilance has become one of my habitual traits. I know no rest. I am always alert and occupied. You must all try to look upon life in this manner, as an eternal student. Ever be keenly on the look-out for learning something new, each day, even each hour. Be like me an intellectual scout. You can learn something from everyone. Everything in this universe has some lesson to give to one who is receptive. Don’t pass by any experience lightly. Draw instruction and inspiration from every great example in the world. Thus perhaps, some chance word of admonition, lost in the subconscious mind, might come up at some critical juncture in one’s life and save us from disaster or change the course of our lives. Extract something from everything and treasure it up in your mind. Carelessness about minor details is not an expression of Vairagya but is a Tamasik habit of neglect.”

He has cultivated the above kind of alert receptivity with care and deliberation. He keeps a recording notebook with him constantly and immediately jots down in it any new idea or thought that occurs to him, any novel suggestion and information given out in his presence. He is convinced that this practice is of immense advantage, both from a spiritual as well as secular point of view.

As a young medico, he used to remain in the hospital even during holidays and instead of wasting away the day, gave his mind wholly to hospital work, study and observation. He would shut out all other thoughts and get immersed in this interesting pursuit. No wonder then that, even as student of the first year, he was well conversant with the entire syllabus of the whole course! This is the key to the apparently effortless and unbroken concentration this Swamiji’s routine life now reveals. I have observed him at times on a settee in the room that serves as office of the Divine Life Society. He would sit there replying to some distant agitated aspirant, answering queries and clearing doubts. A typewriter tattoos away noisily with a nervous rattle, a regular soft ‘thud’, ‘thud’ comes from the next room where somebody is stamping new books with the library seal. From outside, the sound of nails being hammered into a packing case of books, on the road, a few yards away from the room, the loud chant of a batch of pilgrims or the unimaginably deafening din of a passing motor-bus, while from the Ganges is heard the pious shouts of a ferry-boatful of Yatris. As though these were not enough, just near Swamiji squat a party of visitors, one enquiring about a Hindi book, another placing some flowers and fruits on the table, a child becoming restive and talkative, and on the top of all, some hill-man come to ask for some medicine for an ailing daughter; and the figure on the settee quietly absorbed in the work before him, undisturbed in the even and easy flow of his pen. So intent is he on the task that, until the letter is complete, his spectacles removed and restored to its case, and the pen capped and laid down on the table, he is quiet, unaware of those about him. Only when he looks up, sees the visitors, hears the noise, does he say, “Please stop the hammering; ask S. to stamp the books later.”

The development of this sort of one-pointedness is very essential for every aspirant as well as for the layman too. Concentration is not any peculiar ritual or any set exercise to be performed at stated times of the day. It has to become the habitual state of mind of the Sadhaka. Swamiji would state that there is no miraculous short-cut or magical formula for concentration and meditation. It comes naturally to the man who makes it a practice to do even the smallest act with attention and interest. To execute little tasks in a slovenly and careless manner, day by day, renders the mind weak and causes it to lose all acumen and capacity for concentration. He says, “Do you affix a postal stamp to a cover or are you paring a pencil? Well, do it with the same care and minute attention as a jeweller would in setting a diamond to a ring meant for royalty; or as an ophthalmic surgeon would execute a delicate eye-operation. Do everything that you do–eating, cleaning the teeth, reading, writing, even wiping a shoe–with your whole mind and attention. Concentration will develop most effectively.”

Pavhari Baba, the saint of Gazipur, used to give similar advice to aspirants, i.e., to do even the least and the smallest of acts as though the very life depended upon doing it. Forget everything else beside the immediate task on hand.

With Swamiji as a doctor on the F.M.S. (after his student days), we witness the same absorption in his medical and philanthropic activities. And it brought him unscathed through that decade of Malayan life, a life which used invariably to prove disastrous to the morals of most newcomers; for these islands of the Archipelago were to the enterprising Indians what Honolulu and Tahiti were to unguarded Westerners.

Of course, in the case of the spiritual aspirant, the object of concentration as well as the attitude with which it is pursued will necessarily have to be tinged with religious colouring. He has to connect everything with this spiritual ideal.